Paper may be a naturally recyclable product, but the ongoing health and renewal of the resource from which it’s made takes stewardship and care from the paper industry. Historically, sustainable forest management has required foresters to do difficult and time-consuming labor—often tedious, sometimes dangerous. Tracking invasive species, diseases and wildfire risks on the ground. Measuring soil health and tree growth with specialized tools. Surveying hundreds of acres on foot.

In recent years, however, advancements in technology have revolutionized the way our industry manages and sustains healthy forests.

Applications of Drones in Forestry

Unmanned aerial vehicles—drones, to the rest of us—are now used to collect forest data quickly and efficiently. With high-resolution cameras and artificial intelligence capabilities, they’re able to monitor forests more closely than the human eye ever could. Some drones can sense changes in trees’ appearance and immediately notify foresters. Others can plant seedlings in areas that are difficult for foresters to reach.

Domtar’s Ashdown Mill in Arkansas has been using drone technology since 2016, and it currently has two drones to help complete a number of tasks. When ips beetles burrow beneath tree bark and tunnel through pines and spruces, they can damage and even kill the trees. Flying above the forest canopy, Domtar’s drones can check for infestations in half an hour, not half a day.

Monitoring recently planted trees once required foresters to spend hours walking the forest floor, painstakingly recording seedling activity. Drones can now do it in minutes.

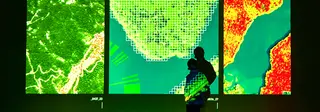

For both foresters and the trees in their care, drones are a lifesaver, making measurements more precise and data more accurate. But our industry goes a step further—or, well, higher—than drones. We also rely on the sky-high, data-driven perspective of satellites. Geospatial technology helps us collect data about forests on an even larger and more detailed scale. It’s a boon for forests’ present and future, helping us analyze their current situation, predict future states and recommend optimal solutions based on inputs.

Satellite Monitoring for Forest Management

Jacob Cude, a senior geospatial analyst, saw firsthand the benefits of satellite technology for forest health during his time at Georgia-Pacific. “It gives us a perspective of that larger scale to make decisions on how to manage our resources, how to make proper ethical business decisions about where we should harvest, where we have harvested, where we shouldn’t,” he says. In short, it informs us on “how to be stewards of the environment.”

Geospatial analysts in our industry can look at a satellite image and discern, for instance, the growth stage of a forest, whether its trees have been planted by hand or machine and if the land’s topography is suitable for agriculture. Cude has been able to answer the questions that define our industry’s relationship with forests: “Are we over- or under-harvesting? Are we doing a good job of maintaining a sustainable use of this resource?”

Geospatial technology doesn’t just benefit trees, but wildlife and water, too. We can analyze the recent harvest of a pine forest and see how foresters have left some of the canopy to preserve a habitat for birds. We can more easily maintain a riparian buffer, the natural vegetation on the edge of a stream that keeps out pollutants, controls erosion and provides habitat and nutrients for the watershed.

“Part of our practice in the forest industry is to not harvest timber within a certain distance of streams, for water quality and water management purposes,” Cude says, “so you don’t pollute rivers, streams and lakes.” He adds, “And that’s standard across the industry.”

A few years ago, Georgia-Pacific launched its endangered forest program, partnering with environmental groups to identify what Cude calls “environmentally significant areas”—stands or forests with special ecological value. They might contain old-growth hardwoods or be meaningful wilderness areas or habitats for endangered species. Using geospatial technology, we can map out these areas in dialogue with foresters on the ground.

“All the areas and species of concern that may be threatened or endangered, their locations are documented spatially within GIS [geographic information systems],” says Alex Singleton, the fiber supply manager of the International Paper containerboard mill in Rome, Georgia. “Maybe there’s a red-cockaded woodpecker that’s been seen on that site. I can pull up our GIS layer and give [my co-worker] the information about that species so that he can identify it if he sees it out in his timber stand.”

Much of the data used in our industry’s geospatial technology comes from Planet, a satellite imagery company led by former NASA employees. Planet’s founding mission was to “image the entire earth on a daily basis … so that people could see what was going on,” Cude says. “So that they can help the environment, preserve the environment—save the planet, basically.”

Pulp- and papermakers, Cude says, are “doing everything they can for the regrowth of trees.” They recognize “the importance of protecting, preserving, conserving and sustainable practices in the industry.”

That recognition is the reason why our industry continues to develop new forest management technology. We rely on trees as much as trees rely on us, so we’re using everything at our disposal to ensure that forests continue to flourish for decades—centuries—to come.